In a Mishnah that we learned two days ago, we read that any additions to the area of either Jerusalem or the Temple Courtyard had to be accompanied by certain attendees and specific offerings:

משנה שבועות יד, א

שֶׁאֵין מוֹסִיפִין עַל הָעִיר וְעַל הָעֲזָרוֹת אֶלָּא בְּמֶלֶךְ וְנָבִיא וְאוּרִים וְתוּמִּים וְסַנְהֶדְרִין שֶׁל שִׁבְעִים וְאֶחָד, וּבִשְׁתֵּי תּוֹדוֹת וּבְשִׁיר

Additions can be made to the city of Jerusalem or to the Temple courtyards only by a special body comprising the king, a prophet, the Urim VeTummim, and the Sanhedrin of seventy-one judges, and with two thanks-offerings and with a special song.

On today’s page of Talmud we learn more from a Baraita about the identity of that “special song.”

שבועות טו, ב

וּבְשִׁיר. תָּנוּ רַבָּנַן: שִׁיר שֶׁל תּוֹדָה – בְּכִנּוֹרוֹת וּבִנְבָלִים וּבְצֶלְצֶלִים עַל כל פִּינָּה וּפִינָּה וְעַל כל אֶבֶן גְּדוֹלָה שֶׁבִּירוּשָׁלַיִם, וְאוֹמֵר ״אֲרוֹמִמְךָ ה׳ כִּי דִלִּיתָנִי וְגוֹ׳״, וְשִׁיר שֶׁל פְּגָעִים, וְיֵשׁ אוֹמְרִין שִׁיר שֶׁל נְגָעִים

The Sages taught in a Baraita: They sang the song of thanksgiving, (Ps. 100, which begins: “A psalm of thanksgiving,)” accompanied by harps, lyres, and cymbals, at every corner and upon every large stone in Jerusalem. And they also recited (Ps. 30 which begins): “I will extol You, O Lord, for You have lifted me up,” and the song of evil spirits, (Ps. 91, which begins: “He that dwells in the secret place of the Most High.)” And some say that this psalm is called the song of plagues.

Psalm 91 - The Song of Plagues

In Jewish traditions, (including those of Ashkenaz, Yemen, Sefarad and North Africa) Psalm 91 is recited on several occasions. On Shabbat and Chagim in the morning service, it is added to the psalms of praise (פסוקי דזימרה). It is part of the prayers recited before sleep, and at Ma’ariv on Saturday night. It is also chanted at a Jewish burial. (You can hear many of the different ways in which various communities chant this Psalm on a charming website from the Jewish National Library here). But why does the Baraita call it The Song of Evil Spirits or The Song of Plagues?

Psalm 91 lists a number of dangers and tragedies that the psalmist faced. Snares and night terrors, “the arrow that flies at day, the plague that stalks in the darkness, and the scourge that rages at noon.” “In all likelihood” wrote the biblical scholar Robert Alter in his 2007 work (The Book of Psalms: A Translation with Commentary (322),

..the setting evoked is a raging epidemic in which vast numbers of people all around are fatally stricken. The image of martial danger, however, introduced by the flying arrow of verse 5 and the shield and buckler of verse 4, is superimposed on the image of danger from the plague, life imagined as a battlefield fraught with dangers.” But for those who trust in God, wrote the psalmist “no harm will befall you, nor will affliction draw near to your tent.”

Here is the full text of Psalm 91, so you get a sense of what Alter is talking about:

יֹשֵׁב בְּסֵתֶר עֶלְיוֹן בְּצֵל שַׁדַּי יִתְלוֹנָן׃

O you who dwell in the shelter of the Most High

and abide in the protection of Shaddai—

אֹמַר לַיהֹוָה מַחְסִי וּמְצוּדָתִי אֱלֹהַי אֶבְטַח־בּוֹ׃

I say of the LORD, my refuge and stronghold,

my God in whom I trust,

כִּי הוּא יַצִּילְךָ מִפַּח יָקוּשׁ מִדֶּבֶר הַוּוֹת׃

that He will save you from the fowler’s trap,

from the destructive plague.

בְּאֶבְרָתוֹ יָסֶךְ לָךְ וְתַחַת־כְּנָפָיו תֶּחְסֶה צִנָּה וְסֹחֵרָה אֲמִתּוֹ׃

He will cover you with His pinions;

you will find refuge under His wings;

His fidelity is an encircling shield.

לֹא־תִירָא מִפַּחַד לָיְלָה מֵחֵץ יָעוּף יוֹמָם׃

You need not fear the terror by night,

or the arrow that flies by day,

מִדֶּבֶר בָּאֹפֶל יַהֲלֹךְ מִקֶּטֶב יָשׁוּד צהֳרָיִם׃

the plague that stalks in the darkness,

or the scourge that ravages at noon.

יִפֹּל מִצִּדְּךָ אֶלֶף וּרְבָבָה מִימִינֶךָ אֵלֶיךָ לֹא יִגָּשׁ׃

A thousand may fall at your left side,

ten thousand at your right,

but it shall not reach you.

רַק בְּעֵינֶיךָ תַבִּיט וְשִׁלֻּמַת רְשָׁעִים תִּרְאֶה׃

You will see it with your eyes,

you will witness the punishment of the wicked.

כִּי־אַתָּה יְהֹוָה מַחְסִי עֶלְיוֹן שַׂמְתָּ מְעוֹנֶךָ׃

Because you took the LORD—my refuge,

the Most High—as your haven,

לֹא־תְאֻנֶּה אֵלֶיךָ רָעָה וְנֶגַע לֹא־יִקְרַב בְּאהֳלֶךָ׃

no harm will befall you,

no disease touch your tent.

כִּי מַלְאָכָיו יְצַוֶּה־לָּךְ לִשְׁמרְךָ בְּכל־דְּרָכֶיךָ׃

For He will order His angels

to guard you wherever you go.

עַל־כַּפַּיִם יִשָּׂאוּנְךָ פֶּן־תִּגֹּף בָּאֶבֶן רַגְלֶךָ׃

They will carry you in their hands

lest you hurt your foot on a stone.

עַל־שַׁחַל וָפֶתֶן תִּדְרֹךְ תִּרְמֹס כְּפִיר וְתַנִּין׃

You will tread on cubs and vipers;

you will trample lions and asps.

כִּי בִי חָשַׁק וַאֲפַלְּטֵהוּ אֲשַׂגְּבֵהוּ כִּי־יָדַע שְׁמִי׃

“Because he is devoted to Me I will deliver him;

I will keep him safe, for he knows My name.

יִקְרָאֵנִי וְאֶעֱנֵהוּ עִמּוֹ־אָנֹכִי בְצָרָה אֲחַלְּצֵהוּ וַאֲכַבְּדֵהוּ׃

When he calls on Me, I will answer him;

I will be with him in distress;

I will rescue him and make him honored;

אֹרֶךְ יָמִים אַשְׂבִּיעֵהוּ וְאַרְאֵהוּ בִּישׁוּעָתִי׃

I will let him live to a ripe old age,

and show him My salvation.”

Because of these references, the psalm was called an “amulet psalm,” although on today’s daf the Talmud refers to it as a Song [to Ward Away] Evil Spirits (shir shel pega’im) or a Song [to Ward Away] Plagues (shir shel nega’im).[ii] In it, plague – dever - is personified. It moves unseen and is therefore unstoppable; in its wake “a thousand fall.” Then something extra happened; by reciting it, the psalm took on magical properties, as we read on today’s daf:

רַבִּי יְהוֹשֻׁעַ בֶּן לֵוִי אָמַר לְהוּ לְהָנֵי קְרָאֵי, וְגָאנֵי

Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi would recite these verses to protect himself from evil spirits during the night and fall asleep while saying them.

Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi (c. 220-250 CE), a talmudic sage from the village of Lod would say the psalm as he fell asleep at night, despite objections from his colleagues that it was forbidden to use words of scripture as protection. And according to the Midrash, Moses himself recited this amulet psalm when he ascended Mount Sinai, “because he feared evil spirits”:

במדבר רבה 12:3

וְנֶגַע לֹא יִקְרַב בְּאָהֳלֶךָ, אָמַר רַבִּי יוֹחָנָן, עַד שֶׁלֹא הוּקַם הַמִּשְׁכָּן הָיוּ הַמַּזִּיקִין מִתְגָּרִין בָּעוֹלָם לַבְּרִיּוֹת, וּמִשֶּׁהוּקַם הַמִּשְׁכָּן שֶׁשָּׁרָה הַשְּׁכִינָה לְמַטָּה, כָּלוּ הַמַּזִּיקִין מִן הָעוֹלָם, הֲדָא הוּא דִכְתִיב: וְנֶגַע לֹא יִקְרַב בְּאָהֳלֶךָ, זֶה אֹהֶל מוֹעֵד. אָמַר רַבִּי שִׁמְעוֹן בֶּן לָקִישׁ מַה לְּךָ אֵצֶל סֵפֶר תְּהִלִּים, וַהֲלֹא בִּמְקוֹמוֹ אֵינוֹ חָסֵר (במדבר ו, כד): יְבָרֶכְךָ ה' וְיִשְׁמְרֶךָ, מִן הַמַּזִּיקִין, אֵימָתַי, וַיְהִי בְּיוֹם כַּלּוֹת משֶׁה, מַהוּ בְּיוֹם כַּלּוֹת, שֶׁכָּלוּ הַמַּזִּיקִין מִן הָעוֹלָם

And no plague will come near your tent” (Psalms 91:10) – Rabbi Yochanan said: Until the Tabernacle was erected, the demons would provoke people in the world. When the Tabernacle was erected, when the Divine Presence rested below, the demons were eliminated from the world. That is what is written: “And no plague will come near your tent” – this is the Tent of Meeting. Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said: Why must you go to the book of Psalms? In its place it is not lacking: “May the Lord bless you and protect you” (Numbers 6:24). When? “It was on the day that Moses concluded.” What is “the day that [Moses] concluded [kalot]’? It means that all the demons were eliminated [shekalu] from the world.

Rabbi Yehoshua’s custom spread in the period following the final editing of the Talmud, an era roughly from 590-1040 C.E. and known as the period of the Ge’onim. It was sometime during this period that Psalm 91 was incorporated into a prayer that is now completely forgotten: Havdala de Rabbi Akiva.

The Forgotten Havdalah of Rabbi Akiva

The composition is a lengthy addendum to the traditional brief prayer, the havdala, said over wine, a candle and spices at the end of the Sabbath and Chagim. The Havdala de Rabbi Akiva was part prayer and part incantation, whose purpose was to ward off witchcraft and evil spirits for the week that lay ahead. Although not recited today, the Havdala de Rabbi Akivah spread from Babylonia to Italy and Spain, and from there to the Jewish communities of Ashkenaz living in the Rhineland. In it, Psalm 91 was recited in its entirety, with the names of God and several angels additionally woven into each verse.

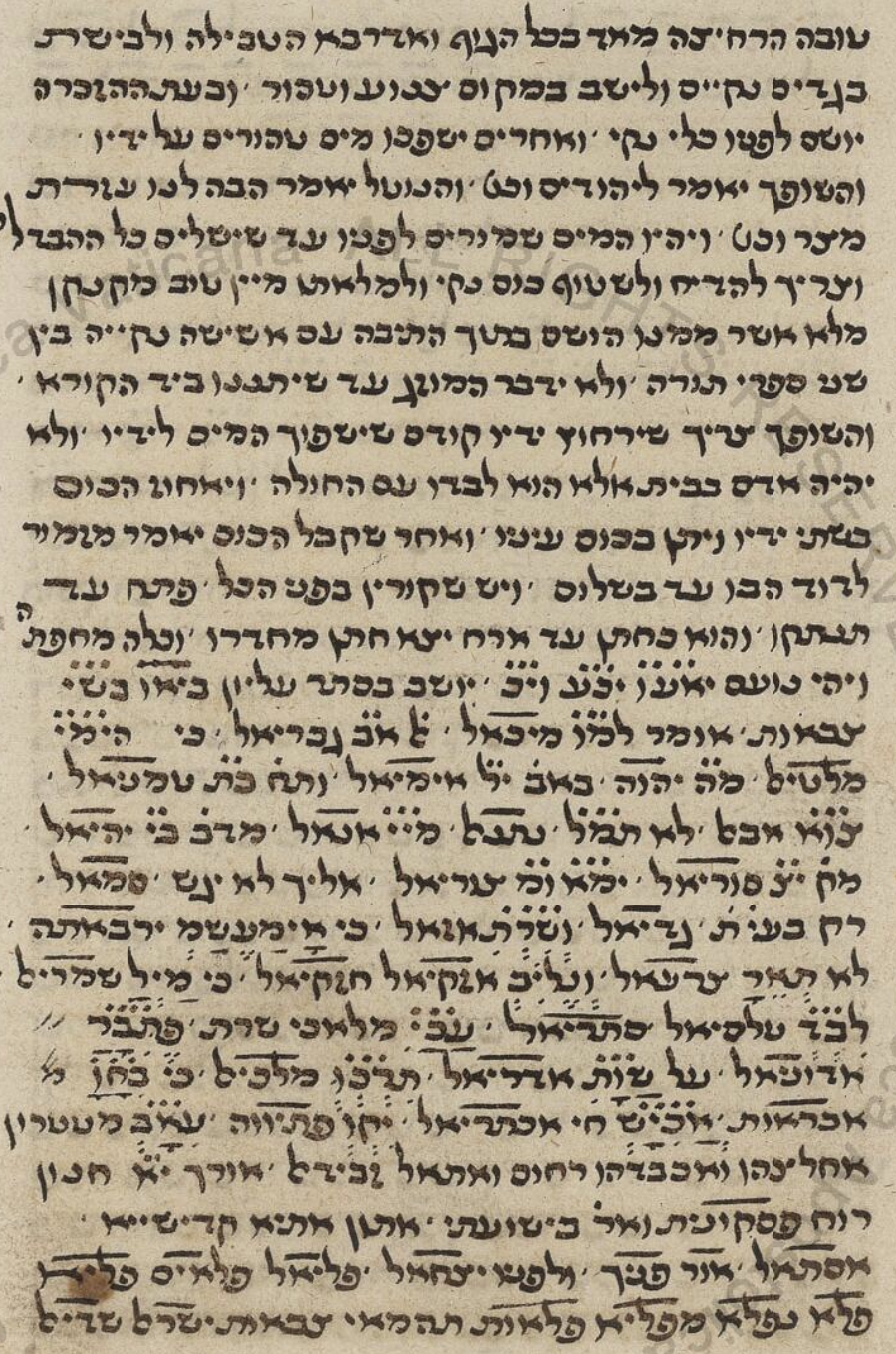

The full text of the Havdalah of Rabbi Akiva can be found in several Hebrew manuscripts, although they differ in many places. This one, from the collection of the Vatican (ebr. 228 93r-98v), is dated 1426-1500:

Havdala de Rabbi Akiva, Vat. ebr. 228.

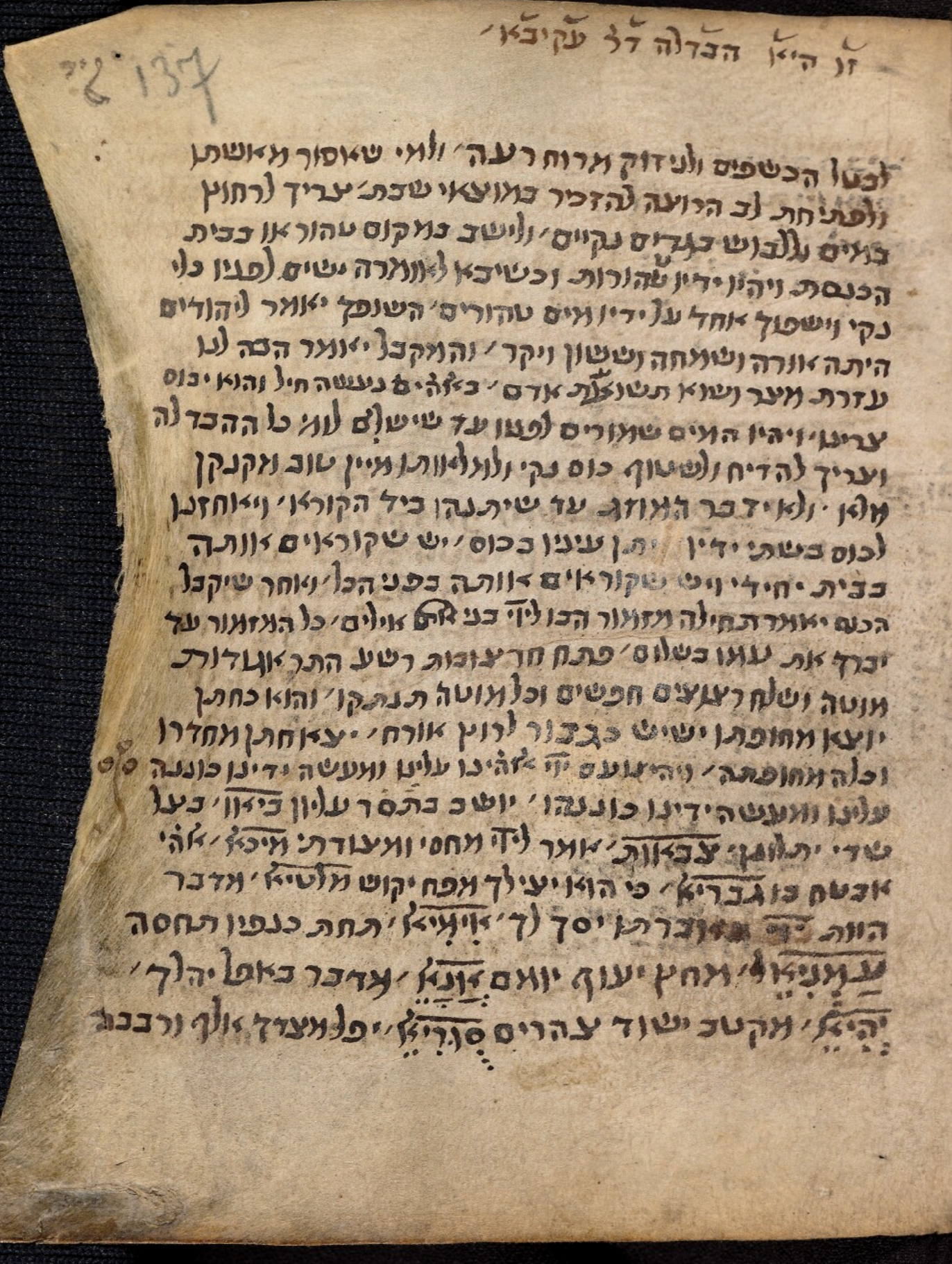

Another version of the text is held at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. It is catalogued as Bodleian Library MS. Michael 9. (Gershon Scholem and others referred to it simply as Oxford MS 1531, when they are referring to what they should have referenced as Neubauer 1531.) The manuscript dates to the early 1300s and is described as “Ashkenazic cursive script, most probably by one hand over a long period.” It contains kabbalistic and Hekhalot texts, the latter being collections of mystical literature, mostly about entering heaven alive, written in late antiquity through to the early Middle Ages. Here is the opening page:

This forgotten Jewish prayer is mentioned in several texts. Rabbi Avraham ben Azriel cites it in his perush on the piyyutim called ערוגת הבושם (Arugot Bosem) written around 1230, and the kabbalist Rabbi Naphtali Hertz of Treves (1473-1540), mentions it in his siddur. (In a long paper on the Havdalah of Rabbi Akiva, that was published posthumously by Gershon Scholem, he notes several other medieval and early modern texts that mention the prayer.) It was also mentioned by the rabbis of Sepharad, such as Shlomo ibn Aderet (1235–1310) known as the Rashba who refers to it in one of his responsa.

The full text is very, very long (Scholem broke it down into 15 sections). You can find it here, and the only attempt of an English translation of which I am aware is here.

זו היא הבדלה דרבי אקיבא

לבטל הכשפים לבטל הכשפים ולניזוק מרוח רעה ולמי שאסור מאשתו ולפתיחת לב

הרוצה להזכיר במוצאי שבת צריך לרחוץ במים וללבוש בגדים נקיים ולישב במקום טהור או בבית הכנסת ויהיו ידיו טהורות. וכשיבא לאומרה ישים לפניו כלי נקי וישפוך אחד על ידיו מים טהורים

השופך יאמר ליהודים היתה אורה ושמחה וששון ויקר. והמקבל יאמר הָבָה לָּנוּ עֶזְרָת מִצָּר וְשָׁוְא תְּשׁוּעַת אָדָם. באלה’ים נעשה חיל והוא יבוס צרינו. ויהיו המים שמורים לפניו עד שישלים לומר כל ההבדלה. וצריך להדיח ולשטוף כוס נקי ולמלאותו מיין טוב מקנקן מלא. ולא ידבר המוזג עד שיתנהו ביד הקורא

This is the Havdalah of Rabbi Akiba to defend against witchcrafts and against injury from an evil spirit, or for [one] who his woman is forbidden him, or to open a heart. The one who desires to remember at the end of Shabbat needs to wash in water and to dress in clean clothes and sit in a pure place or in a synagogue. He will have pure hands. When he is about to recite it, he will place before him a clean vessel and he will pour pure water once upon his hands. The one pouring will recite, “To Jews let there be light, celebration, joy, and dignity,” while the recipient [of the water] will say, “Bring to us help from distress and falsehood; the deliverance of humanity. Through God may we do virtue and may He trample our enemies. And they will be keep the water in front of him until he completes reciting the entire havdalah. And he needs to wash and rinse a cup clean and fill it from a full pitcher of good wine. But the wine-pourer is not to speak until the cup is given in to the hand of the one reciting [the ritual].

And what of Psalm 91, יושב בסתר? Well, it appears, but not in its usual form. Instead, interspersed within the traditional text are a several mystical words, some of which are the names of angels, some of which are names sound like angels. Here it is

יֹשֵׁב בְּסֵתֶר עֶלְיוֹן ביאו בְּצֵל שַׁדַּי יִתְלוֹנָן צבאות׃ אֹמַר לַיהֹוָה מַחְסִי וּמְצוּדָתִי מיכאל. אֱלֹהַי אֶבְטַח־בּוֹ גבריאל׃ כִּי הוּא יַצִּילְךָ מִפַּח יָקוּשׁ מלטיאל מִדֶּבֶר הַוּוֹת יהוה ׃ בְּאֶבְרָתוֹ יָסֶךְ לָךְ אימיאל וְתַחַת־כְּנָפָיו תֶּחְסֶה עמניאל צִנָּה וְסֹחֵרָה אֲמִתּוֹ אבאל׃ לֹא־תִירָא מִפַּחַד לָיְלָה נתנאל מֵחֵץ יָעוּף יוֹמָם אנאל׃ מִדֶּבֶר בָּאֹפֶל יַהֲלֹךְ יהיאל מִקֶּטֶב יָשׁוּד צהֳרָיִם סוריאל׃ יִפֹּל מִצִּדְּךָ אֶלֶף צוריאל וּרְבָבָה מִימִינֶךָ אֵלֶיךָ לֹא יִגָּשׁ סמאל׃ רַק בְּעֵינֶיךָ תַבִּיט גדיאל וְשִׁלֻּמַת רְשָׁעִים תִּרְאֶה אזאל׃ כִּי־אַתָּה יְהֹוָה מַחְסִי י’י צבאות עֶלְיוֹן שַׂמְתָּ מְעוֹנֶךָ ירבאתה׃ לֹא־תְאֻנֶּה אֵלֶיךָ רָעָה צדעיאל וְנֶגַע לֹא־יִקְרַב בְּאהֳלֶךָ אזקיאל חזקיאל׃ כִּי מַלְאָכָיו יְצַוֶּה־לָּךְ שומריאל לִשְׁמרְךָ בְּכל־דְּרָכֶיךָ שלהיאל סרתיאל׃ עַל־כַּפַּיִם יִשָּׂאוּנְךָ מלאכי השרת פֶּן־תִּגֹּף בָּאֶבֶן רַגְלֶךָ אדוניאל׃ עַל־שַׁחַל וָפֶתֶן תִּדְרֹךְ אדריאל תִּרְמֹס כְּפִיר וְתַנִּין מלכיאל׃ כִּי בִי חָשַׁק וַאֲפַלְּטֵהוּ אבראות אֲשַׂגְּבֵהוּ כִּי־יָדַע שְׁמִי חי אכתריאל׃ יִקְרָאֵנִי וְאֶעֱנֵהוּ יה פתי?וה עִמּוֹ־אָנֹכִי בְצָרָה מטטרון אֲחַלְּצֵהוּ וַאֲכַבְּדֵהוּ רחום זיותאל זכוריאל׃ אֹרֶךְ יָמִים אַשְׂבִּיעֵהוּ רוח פיסקונית וְאַרְאֵהוּ בִּישׁוּעָתִי ברחמים׃